Executive Summary

Australia's critical infrastructure is exposed to an increasingly complex and evolving threat landscape. The convergence of risks, particularly cyber threats exacerbated by AI and the looming potential of quantum computing, have elevated the urgency for robust, and proactive risk management and crime prevention strategies across sectors. Critical infrastructure is particularly vulnerable to threats as their operational interdependencies and national significance would create significant challenges for Australia’s security if affected.

The Security of Critical Infrastructure Act 2018 (SOCI Act) provides the legislative foundation for protecting these assets. It mandates that responsible entities implement a Critical Infrastructure Risk Management Program (CIRMP), report cybersecurity incidents, and comply with enhanced obligations for systems deemed to be of national significance. The scope of the SOCI Act spans multiple critical sectors, ensuring that entities are held to consistent standards of resilience and accountability. The CIRMP framework requires entities to identify and manage risks arising from four key hazard vectors: cyber and information security, personnel threats, supply chain vulnerabilities, and physical or natural hazards (CISC, 2025, p.2).

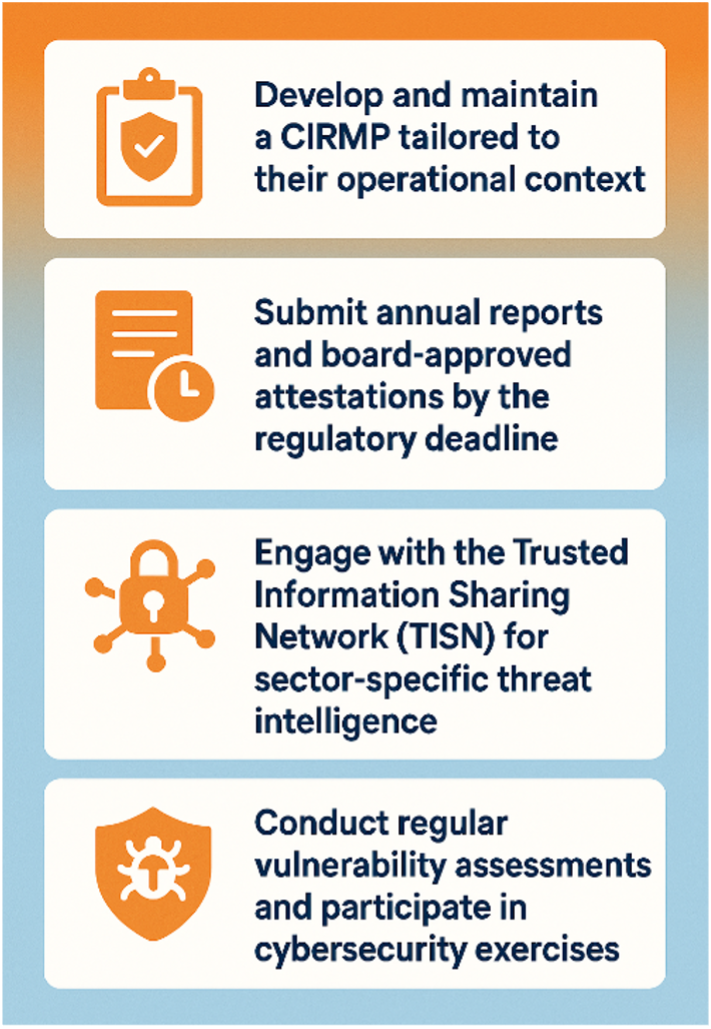

To ensure critical infrastructure owners and operators are within compliance and reduce the risks to their critical assets, recommended actions have been included in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Recommendations to ensure compliance and reduce risks.

To summarise, the SOCI Act and CIRMP obligations represent a strategic shift toward integrated, all-hazards risk management. Entities must not only comply with regulatory requirements but also foster a culture of resilience and preparedness to safeguard Australia’s critical infrastructure in an era of ever-increasing threats.

Context

According to the Critical Infrastructure Security Centre under the Department of Home Affairs, critical infrastructure is defined as being “those physical facilities, systems, assets, supply chains, information technologies and communication networks which, if destroyed, degraded, compromised, or rendered unavailable for an extended period, would significantly impact the social or economic wellbeing of Australia as a nation, or its states or territories, or affect Australia’s ability to conduct national defence and ensure national security” (CISC, 2023, p.4).

In a time where sabotage represents a growing threat to Australia’s critical infrastructure and broader security landscape, particularly seen through cyberattacks (Burgess, 2025), it has never been more essential to protect and strengthen the security of our critical infrastructure against the evolving threats that continue to emerge at rapid rates. An increasingly alarming threat to Australian critical infrastructure which should take priority concern is advanced persistent threats conducted by state-sponsored actors who use highly advanced tactics, techniques, and procedures to infiltrate confidential networks (Makoshi, 2025, p.2). There is also a growing risk of supply chain attacks where attackers compromise third-party vendors and Managed Service Providers to gain access into diverse critical infrastructure networks (Makoshi, 2025, p.4). State-sponsored actors conducting supply-chain attacks represent the gateway to attacks such as sabotage of major critical infrastructure assets and can have substantial cascading impacts on Australia’s security (Makoshi, 2025, p.4). ASIO Director-General Mike Burgess has raised recent concerns over foreign probes into Australian critical infrastructure sectors including water, transport, telecommunications, and energy (Knott, 2025). Burgess has highlighted the threat of highly sophisticated reconnaissance tradecraft to penetrate, maintain undetected access, and sabotage critical networks that would severely implicate Australia’s security if a successful attack were to occur (Knott, 2025). He states escalating geopolitical tensions have created a greater likelihood of such attacks, with attempts to scan and penetrate critical infrastructure in Australia and other Five Eyes countries occurring more frequently (Knott, 2025). This growing threat to Australia’s critical infrastructure must be mitigated and the SOCI Act establishes necessary steps to protecting Australia’s security and critical capabilities.

The Critical Infrastructure Annual Risk Review 2025 (Critical Infrastructure Security Centre, 2025a) notes the vulnerability of critical infrastructure networks that are being targeted by malicious actors within an increasingly tense geopolitical environment. While cyber incidents remain the fastest growing threats to Australia, the technology and supply chain dependencies also mean that inadvertent human error or system failures have proven to be just as disruptive and damaging as malicious attacks (Critical Infrastructure Security Centre, 2025a, p.2). The 2025 risk landscape has changed to one where cyber risks are characterised by the surge in incidents, third-party vulnerabilities and risks from IT, OT and IoT integration, while the rapid increase in the use of AI in cyber offense has created new risks (Critical Infrastructure Security Centre, 2025a, pp.11-13). Where it concerns supply chains, global dependencies and opaque digital supply chains create vulnerabilities, while fuel security remains critical (Critical Infrastructure Security Centre, 2025a, pp.15-17). On the physical security front, sabotage and foreign interference are rising, while the dominant threat is lone-actor extremism which has morphed beyond traditional conceptions and labels (Critical Infrastructure Security Centre, 2025a, pp.19-21). Climate change is leading to an increase in extreme weather events which is resulting in cascading impacts (Critical Infrastructure Security Centre, 2025a, pp.23-25). Personnel risks impacting critical infrastructure include human error, contractor risks, skill shortages and the misuse of AI/deepfakes (Critical Infrastructure Security Centre, 2025a, pp.27-29). The most plausible risks identified in this report are third-party cyber risk, unexpected severe weather location and frequency, significant disruption from infrastructure interdependencies, extreme-impact cyber incident, and geopolitically driven supply chain disruptions (Critical Infrastructure Security Centre, 2025a, p.7). Furthermore, the most damaging risks include extreme-impact cyber incident, IT/OT/IoT connectivity, fuel supply disruption, state-sponsored sabotage, and cascading infrastructure failures (Critical Infrastructure Security Centre, 2025a, p.7). Finally emerging risk drivers include single-source supplier reliance, regional conflict, rising sabotage, unpredictable agentic AI, space tech dependencies, and the urgency of post-quantum cryptography (CISC, 2025, pp.31-32).

The Australian Signals Directorate identifies critical infrastructure as being particularly susceptible to regular targeting from malicious cyber actors due to the critical and essential services they offer as well as the sensitive data they manage (ASD, 2024). Threats to Australia’s critical infrastructure arise from espionage groups, individuals preparing for disruptive attacks, and actors driven by financial motives. The 2024-2025 Annual Cyber Threat Report indicates that state-sponsored cyber actors remain the predominant threat, consistently targeting critical infrastructure networks. Their activities are aimed at disrupting essential services and communications to gain strategic advantages on Australia’s national policies and decision-making through cyber operations (ASD, 2025). Current data indicates that 13% of cybersecurity incidents in Australia involve critical infrastructure, a figure likely to rise as the threat landscape evolves. The three most prevalent reported types of cyber security incidents for critical infrastructure include compromised asset/network/infrastructure making up 55%, Denial of Service (DoS)/Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) making up 23%, and compromised account/credentials making up 19% of incidents (ASD, 2025). The 3 most common activities leading up to these incidents occurred through scanning or reconnaissance making up 41%, DoS/DDoS making up 31%, and phishing attacks making up 20% of all activities (ASD, 2025). Due to the evolving complexity, increasing frequency, and detrimental impact of threats, compliance with the SOCI Act & CIRMP has become increasingly urgent for the security of critical infrastructure.

The SOCI Act contains six key objectives as part of their comprehensive risk management strategy, including to:

- Improve Transparency

- Facilitate Cooperation

- Mandate Risk Management

- Strengthen Cybersecurity

- Extend security obligations to Telecommunications

- Enable Government Response

The most recent amendment of the SOCI Act in March 2024, increased the number of sectors deemed as critical infrastructure from 4 to 11. The sectors now classed as critical infrastructure include Communications, Data Storage and Processing, Defence Industry, Energy, Financial Services and Markets, Food and Grocery, Health Care and Medical, Higher Education and Research, Space Technology, Transportation, and Water and Sewerage (CISC, 2025, p.3). These new critical infrastructure sectors come with additional asset classes which are required to comply with CIRMP.

The SOCI Act 2018: Key Provisions

The Security of Critical Infrastructure Act 2018 (SOCI Act) establishes a central legislative framework designed to protect critical infrastructure across multiple sectors in Australia through imposing security, risk management and reporting obligations for responsible entities. It emphasises an all-hazards approach aimed at creating resilience and strengthen capabilities, ensuring responsible entities and infrastructure assets remain adaptive to emerging threats and enhance Australia’s critical infrastructure security posture. The Cyber and Infrastructure Security Centre (CISC) is under the Department of Home Affairs and is the body responsible for enforcing compliance with the SOCI Act (Nayak, 2025).

The Security of Critical Infrastructure (SOCI) and Other Legislation Amendment (Enhanced Response and Prevention) Act 2024 has introduced recent amendments to the SOCI Act (Security of Critical Infrastructure and Other Legislation Amendment (Enhanced Response and Prevention) Act 2024, 2024). These amendments have significantly altered and expanded the regulatory scope and enforcement mechanisms or the SOCI framework. Key amendments to the SOCI Act include:

- The inclusion and enhanced regulation of additional critical infrastructure sectors and assets.

- Expanded cyber security and incident response obligations as responsible entities for systems of national significance (SoNS) must comply with statutory incident response planning by reporting incidents within 30 days.

- Enhanced ministerial direction powers and overall increase in government authority allows for the management of entities not in compliance with reporting requirements.

- Mandated establishment of a Critical Infrastructure Risk Management Program (CIRMP) (Kewalramani, 2025).

- Mandated reporting of operational information including critical infrastructure assets to the Register of Critical Infrastructure Assets.

CIRMP Requirements

When establishing a Critical Infrastructure Risk Management Program (CIRMP), entities must identify their operational contexts and material risks. The CIRMP should minimise or aim to eliminate risks where reasonably possible as well as mitigate the impact of hazards including attacks on critical infrastructure (Security of Critical Infrastructure (Critical Infrastructure Risk Management Program) Rules (LIN 23/006) 2023, 2025). It is essential that the CIRMP be maintained through regular reviews and updated depending on new capabilities, threats to critical infrastructure, and new regulatory compliance which may change the technicalities of establishing a CIRMP. Understanding what entities need to do to comply with the SOCI Act may not come easily, so for the purpose of digestibility and ease of understanding, the requirements will be outlined below.

Determining Applicability

The first step responsible entities must do is to check if their organisation contains any asset classes deemed as ‘critical’ according to the Cyber and Infrastructure Security Centre (CISC, 2025, p.3) including:

- Electricity, gas, liquid fuels, water assets

- Financial market infrastructure used in connection to payment systems

- Data storage and/or processing systems

- Telecommunications, broadcasting, domain name systems

- Food and grocery

- Designated hospitals

- Freight infrastructure assets/services

Develop a Critical Infrastructure Risk Management Program (CIRMP)

The SOCI Act amendment requires all critical infrastructure operators and owners to develop and maintain a written CIRMP (Slattery, 2023). Whilst compliance with CIRMP obligations is not enforceable, it is highly recommended as it safeguards critical infrastructure assets in the case of an incident or attack. CIRMPs are a vital component of the SOCI Act, facilitating the identification of risks and guiding investment decisions to safeguard critical infrastructure from potential threats and vulnerabilities (Slattery, 2023). CIRMPs ensure responsible entities take proactive approaches to manage the security of their critical infrastructure assets, working towards identifying, preventing and mitigating risks with an all-hazards approach (CISC, 2025, p.2).

Once responsible entities identify their asset(s) as being critical and under CIRMP obligations, the critical infrastructure owners and operators must then conduct the steps identified in Figure 2 as part of their CIRMP.

Figure 2. Essential Requirements for a CIRMP.

It is recommended that any risk management framework be aligned with formal standards such as ISO31000:2018 for an enterprise-wide risk management framework, and ISO27001, NIST Cyber Framework, or the Australian Cyber Security Centre’s Essential Eight (Nayak, 2025) for a cybersecurity/information management framework. ISO27001 is the gold standard for managing and mitigating cybersecurity risks effectively, allowing for structured, well-established, and widely recognised approaches which are not only trusted by regulators, but also protect the cybersecurity of critical infrastructure facilities and assets.

Hazards are defined under 4 categories including: cyber and information security hazards, personnel hazards, physical security and natural hazards, and supply chain hazards (CISC, 2025, p.5).

Cyber and Information Security hazards

To manage cyber and information security hazards, an entity must establish and maintain a process or system in the CIRMP to minimise or eliminate any material risk of a hazard occurring and must mitigate the impact of the hazard on the CI asset as much as reasonably practicable (CISC, 2025, p.8). Starting from 2024-2025, entities are now required to report on their cyber security framework. Acceptable frameworks include the Australian Standard AS ISO27001, Essential Eight Maturity Model by the Australian Signals Directorate, Improving Critical Infrastructure Cybersecurity by the National Institute of Standards and Technology of the United States of America, the Cybersecurity Capability Maturity Model by the Department of Energy of the United States of America, and the 2020-21 AESCSF Framework Core published by Australian Energy Market Operator Limited (CISC, 2025, p.9). Some hazards to consider include phishing attacks, malware, credential harvesting, which is often conducted through phishing, Denial-of-Service (DoS) attacks which disable systems by overloading them with requests, and supply-chain vulnerabilities (CISC, 2025, p.9).

To effectively identify, manage, and act on these risks, advanced methods such as bow-tie analysis, MITRE ATT&CK and FAIR can be employed. The use of bowtie analysis for managing cyber security risks is a recommended strategy to mitigate risk due to its ability to identify major risks, assess strengths and weaknesses of current IT systems, and create general awareness among all key stakeholders (Wheeler, 2024). It works by visually identifying the relationship between potential threats and the resulting consequences. Bowtie analysis result in the implementation of preventative measures against cyber-attacks such as anti-spoofing measures, vulnerability scans, advanced endpoint detection and response measures, and principles of least privilege for user account management (Wheeler, 2024). Bowtie analysis also allows for timely responses after incidents occur by implementing event logging and monitoring capabilities, and creating ransomware incident response plans (Wheeler, 2024). Additionally, this method allows for effective recovery controls to be implemented after a cybersecurity attack to ensure business continuity by minimising operational disruptions and establishing comprehensive backup and recovery mechanisms (Wheeler, 2024). MITRE ATT&CK is another method which supports cyber and information security hazard management. It is globally accessible and is updated with real-world cyber incidents, which information on adversary tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) to help organisations better understand attacker behaviour. FAIR is a model used for understanding, analysing, and quantifying cyber and operational risks in financial terms, and builds a foundation for developing a robust approach to information risk management (Fair Institute, 2025). It is a compliance-based approach which not only provides recommendations but enables an organisation to implement multiple layers of security to adequately protect them against cyber and operational risk (Fair Institute, 2025).

To mitigate against these hazards, there are various strategies an entity can implement to protect their assets. These include anti-phishing techniques such as training employees on how phishing attempts present themselves and how to correctly report suspicious emails within their security network (Lenaerts-Bergmans, 2024). Additionally, developing incident response plans which detail what steps and actions will be taken in response to a cyber security incident is highly recommended as it improves resilience and can reduce the financial costs needed to recover from a cyber-attack. Regular control testing evaluates vulnerabilities in critical applications and systems, as well as penetration testing which is a simulated cyber-attack which targets firewalls, IT, and OT infrastructure (CISC, 2025, p.9). Additionally, implementing Principles of Least Privilege (PoLP) is highly recommended as a risk mitigation strategy as it employs a role-based access control system which limits a user’s account to exactly what permissions they need (NCSC, 2025). It gives the user the minimum number of permissions needed to be able to conduct their job, and this ultimately limits the extent of harms a cyber-attack can conduct if the user account is compromised as attackers can gain access to more data and systems when the account has unrestricted access to an entire system (NCSC, 2025).

Personnel Hazards

Personnel Hazards are those which involved the entity’s critical workers. First, the response entities must identify their critical workers who are employees, interns, contractors, or subcontractors that have access to, control, or management or a critical component of the CI asset, or if their absence or compromise would prevent the CI asset from functioning properly or cause significant damage to the asset (CISC, 2025, p.10). Responsible parties should allow only workers who have been evaluated as suitable to access critical components of the asset for critical work. Another factor entities must implement is to minimise or eliminate material risk as much as reasonably practicable which may arise from malicious or negligent employees or contractors, and outgoing employees or contractors who retain access upon departure (CISC, 2025, p.10).

Entities can mitigate these risks via restricting access control both physically and digitally, to only authorised individuals. Principles of least privilege are recommended to ensure only necessary individuals have access to the CI asset. Additionally, background checking critical workers is another recommendation for reducing the risk of malicious activity or sabotage from within the entity. Background and financial checks should be conducted regularly, not just prior to employment. This ensures that any changing circumstances that may adversely impact individuals are captured as an active security risk management process. CISC recommends using AusCheck, a service used for mitigating insider risks within Australia’s critical infrastructure sectors by conducting background checks and issuing security identity credentials. Additionally mitigation strategies include heightening personnel monitoring for those who have access to critical systems to detect malicious actors within short amounts of time, as well as enhanced cyber security training for all staff, particularly surrounding common attacks and how to prevent being attacked such as through anti-phishing, password security, and secure data storage training (CISC, 2025, p.10).

Supply Chain Hazards

Supply chains are vital for the continuity of critical infrastructure entities as it involves complex interactions across the lifecycle of all services and products used (Riley, 2022, p.6). According to the Cyber and Infrastructure Security Centre (CISC), a CIRMP must minimise or eliminate material risks arising from the supply chain by implementing and maintaining appropriate processes or systems. These should address issues such as unauthorised access, interference, or exploitation of a critical infrastructure asset’s supply chain; misuse of privileged access; disruptions caused by supply chain matters; reduced capacity or failure of related assets and entities; and risks associated with major suppliers or threats to personnel, assets, equipment, products, services, distribution channels, and intellectual property within the supply chain (CISC, 2025, p.11).

Responsible entities must first understand that constitutes as their supply chain, by identifying major suppliers which the critical infrastructure asset relies on to operate, what processes are necessary to ensure continuity of essential goods and services offered by the CI asset, what essential processes and third parties does the entity rely on, who owns and operates these vendors, and what country do these vendors operate from (CISC, 2025, p.11). Understanding these aspects, allows for an entity to conduct a risk assessment which feeds into an effective risk mitigation plan. Additional mitigation strategies for supply chain hazards include to ensuring major suppliers with access to sensitive data have proficient security personnel and cyber security strength and resilience policies built into contract arrangements to ensure responsibility and accountability. Diversifying vendors to reduce dependencies and supply chain bottlenecks is also a recommended action to be integrated into the entities CIRMP as it will allow the entity to continue providing essential products and services if a supply chain hazard emerges (CISC, 2025, p.11).

Physical Security and Natural Hazards

Physical security hazards are those which involve the unauthorised access to, interference with, or control of CI assets with the aim of compromising the proper function of the asset or cause significant damage to the CI asset. Natural hazards are those including floods, storms, heatwaves, fires, cyclones, space weather, or biological health hazards such as the COVID 19 pandemic (CISC, 2025, p.12). in 2023-2024, physical security and natural hazards were the most common form of incidents which resulted in significant impacts and therefore, it is highly recommended and vital to incorporate a strong CIRMP to mitigate, and build resilience against these risks (CISC, 2025, p.12). To comply with the SOCI Act and their CIRMP, entities must first identify physical critical components of their CI assets before minimising or eliminating the risk that a physical security or natural hazard could have on the CI asset. They must respond to unauthorised access incidents, control the access to physical critical components by allowing only individuals who are critical workers or accompanied visitors into the area, and they must test security arrangements to ensure their detection, deterrence, response, and recovery from a breach will be effective (CISC, 2025, p.12).

Mitigation strategies that are recommended to be adopted include ensuring critical components are constantly patrolled or monitored by security staff, using access privileges and onsite security to lock down industrial control systems such as HVAC, cameras, fire alarm panels from attacks, fostering infrastructure resilience and preparedness through emergency exercise planning, simulations and contingency planning, implementing physical and electronic access control methods such as robust perimeter fencing, biometric access-keys, magnetic locks and timed-lock access, developing bush fire survival plans, de-clustering key assets by maintaining backup infrastructure and spreading infrastructure across multiple sites, and to install video surveillance and security lighting to improve unauthorised access detection (CISC, 2025, p.12). An additional strategy for mitigating natural hazards is to develop effective training programs for staff to understand the risks of disasters as well as how to respond to a hazardous situation (Queensland Fire and Emergency Services, 2024, p.44.) This is vital in strengthening resilience and confidence in understanding disaster management arrangements, which then mitigates the potential impact of natural hazards by improving recovery time.

Enhanced Cyber Security Obligations

ParagrRecent amendments to the SOCI Act have introduced enhanced cyber security obligations in relation to mandated reporting of cyber security incidents. Assets that are now deemed as Systems of National Significance (SoNS), are required to adopt four additional Enhanced Cyber Security Obligations (ECSO) as part of the SOCI Act (CISC, 2023). aph

Designation of SoNS

A critical infrastructure asset may be designated as SoNS if the nature and scope of its interdependencies with other critical infrastructure assets, along with the potential consequences for Australia’s social or economic stability, defence, or national security, would result in a significant relevant impact on the asset should a hazard occur (CISC, 2025a). The designation of SoNS is made by the Minister for Home Affairs under Part 6A of the SOCI Act, following consultation with the responsible entity. When deciding which ESCO to apply to SoNs, the Secretary of the Department of Home Affairs (The Secretary) will consider the likely cost the entity will be required to incur to comply with obligations, the reasonableness and proportionality of the decision, and any other matters deemed relevant (Critical Infrastructure Security Centre, 2025).

The Four ESCO Requirements for Responsible Entities

1. Provide system information to develop and maintain a near-real time threat picture.

This requirement supports proactive monitoring and rapid response to emerging cyber threats. It allows for a more mature understanding of emerging cyber security threats and therefore gives entities the capability to effectively reduce the risks incurred by a significant cyber-attack (Riberio, 2024). System information includes network logs, system telemetry and event logs, alerts, NetFlow and other aggregate or metadata (Critical Infrastructure Security Centre, 2025). No personal information should be included as part of this requirement.

2. Undertake vulnerability assessments of their assets and systems to identify vulnerabilities needed to remediate.

This requirement allows any asset and system weaknesses to be promptly identified and used to inform remediation strategies. This builds resilience and preparedness against cyber incidents and malicious actors (Riberio, 2024). Examples of how vulnerability assessments can be conducted include a documentation-based review of a system’s design, a hands-on assessment, or automated scanning with software tools to identify vulnerabilities (Critical Infrastructure Security Centre, 2025). The Secretary may require systems and either all types of cyber security incidents or one or more specified types of incidents to be assessed as part of this requirement (Critical Infrastructure Security Centre, 2025). Entities may be required to provide the designated officer with access to the premises, computers, and reasonable assistance and facilities that are reasonably necessary for the purposes of undertaking the vulnerability assessment (Critical Infrastructure Security Centre, 2025).

3. Undertake cybersecurity exercises aimed at building cyber preparedness in the case of an attack or system failure.

This requirement is vital in helping to identify vulnerabilities and testing response mechanisms as well as revealing whether existing resources, processes and capabilities are adequate and compliant to efficiently safeguard an entity’s system in the case of a cyber incident (Critical Infrastructure Security Centre, 2025). The exercises may be required to test internal response capability, key staff responsibilities, and coordination mechanisms for general cyber security incidents, or more specific threat scenarios as required by the Secretary (Critical Infrastructure Security Centre, 2025).The entity may be required to allow one or more designated officers to observe the cyber security exercise, provide access to the premises, provide reasonable assistance and facilities, allow them to make records of the exercise for the purpose of monitoring, and provide the designated officer/s with reasonable notice of when the cyber security exercise will begin (Critical Infrastructure Security Centre, 2025).

4. Develop a cyber security incident response plan to strengthen resilience and preparation for a cyber security incident (CISC, 2025a).

This requirement helps entities identify what to do and who to call in the event of a cyber incident. It should consider the services provided by the asset, the extent and nature of interdependencies, and the threat environment to create an effective incident response plan (Critical Infrastructure Security Centre, 2025). A copy of the plan must be provided to the Secretary once it is adopted, and after any changes to the plan occur (Critical Infrastructure Security Centre, 2025).

Common Challenges and Compliance risks

Whilst the SOCI act and CIRMP are vital in critical infrastructure security, there are various common challenges and compliance risks which hinder their ability organisations to understand and implement effective measures. As the SOCI Act is highly complex and has a wide scope of obligations to follow, responsible entities may find it difficult to identify and employ management measures for risks across the four hazard vectors including cyber and information security, personnel, supply chain, and physical and natural hazards, especially for entities with limited resources (CISC, 2025). Ensuring there is internal understanding of the SOCI Act, CRIMP requirements, and the overall importance of implementing features of the act is essential in preventing uncertainty, confusion with how to report, difficulty in producing a unified approach to risk management, and prevents a lack of internal expertise and capability in risk management and mitigation (Nayak, 2025).

There is also the risk of non-compliance with the SOCI Act. If responsible entities conduct late or incomplete annual reporting, they may be hit with civil penalties. The current civil penalty for not adopting and maintaining a CIRMP is up to 1000 penalty units, which is approximately 275,000 AUD for individuals, or up to 1.38 million for corporations, highlighting the importance of maintaining and regularly updating CIRMPs (Silverfort, 2025). Civil penalties will be further discussed in the section below to allow entities to understand the significance and risks of non-compliance.

What happens if I’m not in compliance with the SOCI Act?

If an entity is found to not follow the SOCI Act, there are civil penalties that will be imposed, resulting in significant legal and financial consequences. Not only are there civil penalties that can be enforced through various mechanisms, but the entity may also face operational disruption that compromises effectiveness and supply chains, reputational damage as a result of impacted critical services, and even government intervention as they now have jurisdiction to step in to manage the non-compliant entity (Nayak, 2025).

Civil Penalties

This section outlines the applicable penalties which entities may face if found to be in non-compliance with the SOCI act and CIRMP requirements. It references the SOCI Act 2018, and the CIRMP Rules (LIN 23/006) 2023, detailing which sections in which the breach description and associated penalties can be found. The SOCI act does not come without possible penalties which can be incurred if entities do not properly comply with legislation and requirements. Breaches range from failure to keeping CIRMP up to date, failing to submit CIRMP reports within time frames, failing to submit internal evaluations after mandatory cyber exercises, general enforcement mechanisms, and failure to implement hazard-specific risk controls.

| Legislative Reference1 | Section | Breach Description | Penalty |

| Security of Critical Infrastructure Act 2018 | 30AG | Failure to keep CIRMP up to date | 200 penalty units |

| Security of Critical Infrastructure Act 2018 | 30AG | Failure to submit annual CIRMP report within 90 days | 150 penalty units |

| Security of Critical Infrastructure Act 2018 | 30CP | Failure to undertake a mandated cyber security exercise | 200 penalty units |

| Security of Critical Infrastructure Act 2018 | 30CQ | Failure to submit internal evaluation report after cyber exercise | 200 penalty units |

| Security of Critical Infrastructure Act 2018 | 30EC | Failure to comply with notice for additional information (telecom assets) | 150 penalty units |

| Security of Critical Infrastructure Act 2018 | Part 5 | General enforcement mechanisms: civil penalty orders, injunctions, enforceable undertakings, infringement notices | Variable (based on breach) |

| CIRMP Rules (LIN 23/006) 2023 | 30AH | Failure to implement hazard-specific risk controls (cyber, personnel, supply chain, physical/natural) | Subject to civil penalties |

Conclusion

In summary, critical infrastructure forms the backbone of Australian society and supports essential services. With the growing threat and vulnerability of critical infrastructure to be threatened or attacked by malicious actors, safeguarding these assets is paramount to national security. The SOCI Act and CIRMP framework provides valuable mechanisms and methods of compliance that ultimately protect critical infrastructure. They establish robust compliance mechanisms, empower authorities to intervene when necessary, and encouraging proactive risk management. By providing clear enforcement tools and pathways for remediation, these legislative measures help ensure that Australian critical infrastructure remains resilient against emerging threats and continues to function reliably.

References

- Burgess, M. (2025, February 19). ASIO Annual Threat Assessment 2025. Australian Security Intelligence Organisation, National Intelligence Community. https://www.intelligence.gov.au/news/asio-annual-threat-assessment-2025

- Australian Signals Directorate. (2024, November 20). Annual Cyber Threat Report 2023–2024. Cyber.gov.au. https://www.cyber.gov.au/about-us/view-all-content/reports-and-statistics/annual-cyber-threat-report-2023-2024

- Australian Signals Directorate. (2025, October 14). Annual Cyber Threat Report 2024-2025 | Cyber.gov.au. Cyber.gov.au. https://www.cyber.gov.au/about-us/view-all-content/reports-and-statistics/annual-cyber-threat-report-2024-2025

- Catania, P., North, J., Wheelahan, F., Gay, J., & Allen, C. (2025, May 9). What you need to know about Australia’s critical infrastructure reforms. Corrs Chambers Westgarth. https://www.corrs.com.au/insights/what-you-need-to-know-about-australias-critical-infrastructure-reforms

- Cyber and Infrastructure Security Centre (CISC). (2023, February). Critical Infrastructure Resilience Strategy (pp. 1–16). Australian Government, Department of Home Affairs. https://www.cisc.gov.au/resources-subsite/Documents/critical-infrastructure-resilience-strategy-2023.pdf

- Cyber and Infrastructure Security Centre (CISC). (2025, March). Guidance for the critical infrastructure risk management program. Australian Government. https://www.cisc.gov.au/resources-subsite/Documents/guidance-for-the-critical-infrastructure-risk-management-program.pdf

- Cyber and Infrastructure Security Centre (CISC). (2025a, April). The Enhanced Cyber Security Obligations Framework. In CISC (pp. 1–7). Australian Government, Department of Home Affairs. https://www.cisc.gov.au/resources-subsite/Documents/cisc-factsheet-systems-of-national-significance-enhanced-cyber-security-obligations.pdf

- Critical Infrastructure Security Centre. (2025, August). Enhanced Cyber Security Obligations. Australian Government, Department of Home Affairs. https://www.cisc.gov.au/how-we-support-industry/regulatory-obligations/enhanced-cyber-security-obligations

- Critical Infrastructure Security Centre. (2025a, November). Critical Infrastructure Annual Risk Review. Australian Government, Department of Home Affairs. https://www.cisc.gov.au/resources-subsite/Documents/critical-infrastructure-annual-risk-review-2025.pdf

- Kewalramani, K. (2025). What is the SOCI act? Critical Infrastructure explained. Cyber Ethos. https://cyberethos.com.au/articles/security-of-critical-infrastructure-act-and-its-impact-on-australias-critical-infrastructure/

- Knott, M. (2025, November 12). ASIO boss sounds alarm on ‘devastating, disruptive’ Chinese hacking threat. The Sydney Morning Herald. https://www.smh.com.au/politics/federal/asio-boss-sounds-alarm-on-devastating-disruptive-chinese-hacking-threat-20251111-p5n9am.html

- Lenaerts-Bergmans, B. (2024, October 24). What is phishing? Techniques and prevention. Crowdstrike. https://www.crowdstrike.com/en-us/cybersecurity-101/social-engineering/phishing-attack/

- Makoshi, S. M. (2025). The Evolving Cyber Battlefield: A Comprehensive Analysis of State-Sponsored APTs, TTPs, and Strategic Cyber Defense Mechanisms. Authorea Preprints. https://www.authorea.com/doi/full/10.22541/au.175070902.28093557

- National Cyber Security Centre. (2025). Principles of Least Privilege. NCSC.Govt.nz. https://www.ncsc.govt.nz/protect-your-organisation/principle-of-least-privilege/

- Nayak, R. (2025, July 4). Why the SOCI Act matters now more than ever. Diligent.com. https://www.diligent.com/en-au/resources/blog/what-is-the-soci-act

- Regulatory Powers (Standard Provisions) Act 2014, (Cth). https://www.legislation.gov.au/C2014A00093/latest/text

- Ribeiro, A. (2023, February). Australia’s CISC Provides Guidance on Vulnerability Assessments for Critical Infrastructure Installations. Industrial Cyber. https://industrialcyber.co/regulation-standards-and-compliance/australias-cisc-provides-guidance-on-vulnerability-assessments-for-critical-infrastructure-installations/

- Riley, M. (2022). Enhanced Supply Chain, Personnel and Risk Management Plan Business Case (pp. 1–43). Australian Energy Regulator. https://www.aer.gov.au/system/files/Transgrid%20-%20Enhanced%20Supply%20Chain%2C%20Personnel%20and%20Risk%20Management%20Plan%20Business%20Case%20Rev%201%20-%2011%20Nov%202022%20-%20PUBLIC.pdf

- Security of Critical Infrastructure Act 2018, (Cth). https://www.legislation.gov.au/C2018A00029/latest/text

- Security of Critical Infrastructure (Critical infrastructure risk management program) Rules (LIN 23/006) 2023, (2025). https://www.legislation.gov.au/F2023L00112/latest/text

- Security of Critical Infrastructure and Other Legislation Amendment (Enhanced Response and Prevention) Act 2024, (2024). https://www.legislation.gov.au/C2024A00100/asmade/text

- Silverfort. (2025, June). Comply with the Security of Critical Infrastructure (SOCI) Act Requirements with Silverfort. Silverfort. https://www.silverfort.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/Comply-with-SOCI-with-Silverfort-1.pdf

- Slattery, T. (2023, July 13). Building a risk management program for critical infrastructure | The Strategist. The Strategist; Australian Strategic Policy Institute. https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/building-a-risk-management-program-for-critical-infrastructure/

- Queensland Fire and Emergency Services. (2024). Queensland Critical Infrastructure Disaster Risk Assessment (pp. 1–151). Queensland Fire and Emergency Services. https://www.disaster.qld.gov.au/qermf/Pages/Assessment-and-plans.aspx

- Wheeler, S. (2024, May 10). Leveraging Bow-Tie Analysis for Comprehensive Cyber Risk Management. WorkSafetyPulse.com. https://www.worksafetypulse.com/leveraging-analysis-comprehensive-cyber-risk/