Introduction

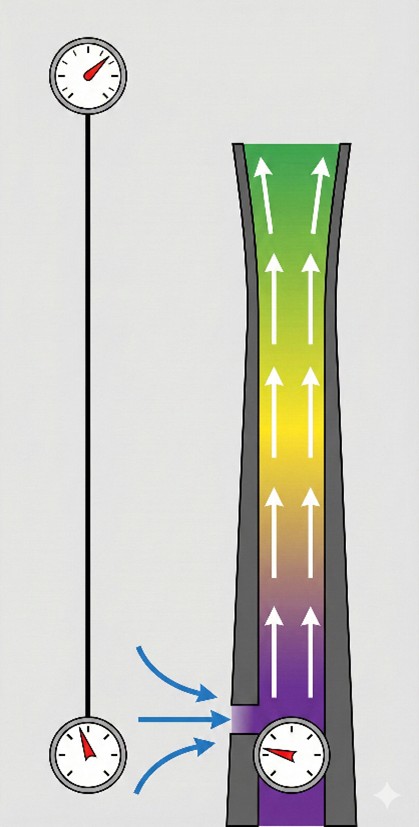

Stack effect, or thermal buoyancy involves the movement of air in and out of buildings, whether through unsealed openings, chimneys, or other purposefully designed openings or containers. It uses the principle of air buoyancy to achieve this (i.e., hot air rises, cool air sinks), where cold air enters through the lower portions of a building and gets pushed upwards, pushing out the hot air (created through heating systems) to the higher portions of a building, causing it to gradually escape through openings and cracks. As hot air is more buoyant than cold air, it will always separate upwards from cooler air.

How Stack Effect Works

Stack effect generally occurs in environments where there is an extreme difference in indoor heat and outdoor heat, as well as additional wind pressure on the external walls of the building. Stack effect, while occurring in most types of buildings to an extent, are especially of concern in high-rise buildings, due to the stack effect being directly proportional to building height and temperature difference between indoor and outdoor environments.

Figure 1. Stack effect air flow

In taller buildings, stack effect leads to many issues that make living/ working unpleasant, such as spontaneous opening of doors, disruptive noises, uncomfortable drafts, increased heating loads, greater spread of pollutants and viruses in the air, and reduced HVAC performance. Generally, these issues are far more pronounced in environments with colder climates such as Korea, Northeastern Asia, North America and Northern Europe, where temperature difference outside and inside reaches over 30°C. In commercial high-rise buildings, improving airtightness of external walls is the most effective way of minimising stack effect, though much less effective for residential floors due to balconies and openings with poor sealing, where improving internal airtightness reduced pressure differences.

In contrast, the stack effect is used in hotter environments to encourage natural ventilation, keeping indoor areas cool. This allows for a cooling system that is both passive, energy efficient and low cost. However, it relies on cool air being pushed into the building through winds, which not every climate has access to. Despite this, it is worth considering in hotter and windier climates.

Stack effect is not the only way in which temperature changes affect buildings. The reverse stack effect acts as the inverse of traditional thermal buoyancy, in which the outside air is warmer than inside air, pushing the airflow downwards. Warmer air enters through openings and cracks in the higher portions of the building and pushes out the cooler air from the lower portions of the building.

Lessons from History and Traditional Design

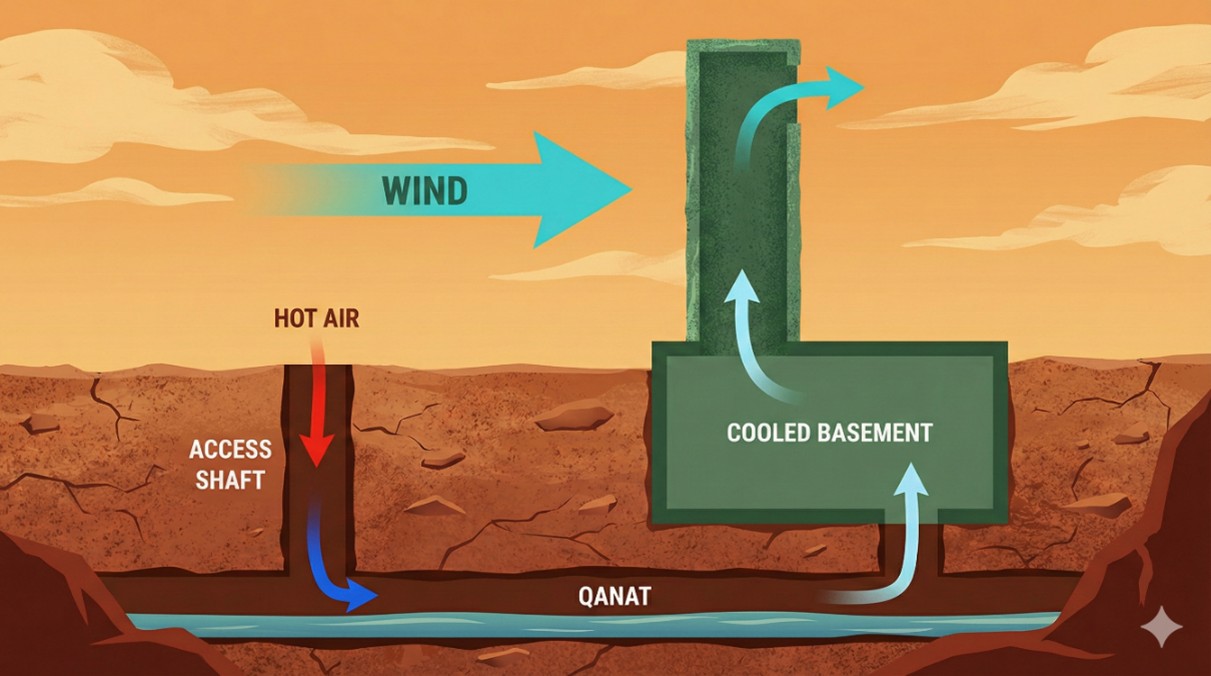

Stack effect has been used intentionally throughout human history, often in tandem with other natural phenomena. Some very famous examples are found in modern day Iran, where the areas in the centre of the country are primarily hot desert landscapes. Specifically, two systems will be discussed here: windcatchers (Badgir) and ice pits (Yakhchal). Both windcatchers and yakhchals rely on the stack effect, evaporative cooling and thermal mass, to function. They are often used in tandem, with windcatchers cooling buildings and water reservoirs (ab anbars), while yakhchals store ice produced during winter for year-round use. The integration of these systems with qanats and thick-walled architecture exemplifies a holistic approach to passive cooling in arid environments. This synergy allowed ancient Persian engineers to create habitable and functional spaces in some of the world’s harshest climates, demonstrating advanced understanding of thermodynamics and sustainable design.

Figure 2. How stack effect works

Stack effect has also led to structural failures, resulting in casualties. One such example is the Kaprun tunnel fire in Austria on 11th November 2000, when an Austrian ski resort railway electric fan heater failed, leading to a fire that resulted in 155 deaths. The fire began when a faulty electric fan heater, designed for domestic use, overheated in the rear control compartment of the train. The heater’s failure ignited leaking hydraulic fluid, producing an intense blaze. As the tunnel sloped upward at approximately 39°C, the train became trapped about 500 metres inside, and the fire rapidly escalated. Stack effect came into play due to the uphill slope, which led to the 3.3 km tunnel becoming a giant chimney, pushing fumes and smoke upwards, choking any passengers escaping upwards that may have survived the initial fire. The emergency open door at the top end of the tunnel being open further acted as a suction which exacerbated the effect.

Conclusion

The stack effect is far more than a curious phenomenon of airflow; it is a critical factor that bridges building physics with modern fire safety engineering. As this article has shown, buoyancy driven air movement can be harnessed for passive cooling in hot climates or, conversely, become a major contributor to discomfort and inefficiency in cold regions. However, its most consequential implications emerge during fire events. The same pressure differentials that naturally move air through buildings can rapidly transport smoke, toxic gases, and heat, turning vertical shafts, stairwells, and tunnels into dangerous chimneys. Incidents such as the Kaprun tunnel fire demonstrate how stack effect can intensify fire spread, overwhelm escape routes, and severely compromise life safety.

For fire safety engineers, understanding stack effect is therefore essential to designing safer buildings and infrastructure. It informs decisions on compartmentation, pressurisation of egress paths, smoke control system design, and the placement of mechanical ventilation. By modelling pressure regimes, anticipating seasonal variations, and integrating both passive and active controls, engineers can mitigate unintended airflow paths and ensure that smoke behaves predictably during emergencies. In this way, the nuanced study of stack effect becomes a foundation for resilient design, transforming a natural physical principle into a tool that protects occupants, supports effective evacuation, and strengthens the overall fire safety performance of buildings.

References

- Bilyaz, S., Buffington, T., & Ezekoye, O. A. (2021). The effect of fire location and the reverse stack on fire smoke transport in high-rise buildings. Fire Safety Journal, 126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.firesaf.2021.103446

- Hamer, M. (2000, November 13). Austrian train tragedy. NewScientist. https://www.newscientist.com/article/dn168-austrian-train-tragedy/

- Jo, J., Lim, J., Song, S., Yeo, M., & Kim, K. (2007). Characteristics of pressure distribution and solution to the problems caused by stack effect in high-rise residential buildings. Building and Environment, 42(1), 263-277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2005.07.002

- Kaprun Disaster. (n.d.). Railsystem.net. Retrieved January 13, 2026, from https://railsystem.net/kaprun-disaster/

- Lim, H., Seo, J., Song, D., Yoon, S., & Kim, J. (2020). Interaction analysis of countermeasures for the stack effect in a high-rise office building. Building and Environment, 168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2019.106530

- Mijorski, S., & Cammelli, S. (2016). Stack Effect in High-Rise Buildings: A Review. International Journal of High-Rise Buildings, 5(4), 327-338. https://doi.org/10.21022/IJHRB.2016.5.4.327

- Shabestan. (n.d.). Wikipedia. Retrieved January 13, 2026, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shabestan

- Stack effect. (n.d.). Wikipedia. Retrieved January 13, 2026, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stackeffect

- Windcatcher. (n.d.). Wikipedia. Retrieved January 13, 2026, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Windcatcher