Introduction

Australia’s terrorism threat level is PROBABLE, meaning there is a greater than fifty percent chance of an offshore attack or attack being planned in the next twelve months, with lone-actor, low sophistication attacks most likely to occur in crowded places (National Native Title Tribunal, 2024).

The Evolution of Modern Terrorist Tactics

Understanding today’s threat environment requires recognising how modern terrorist tactics have evolved and how the attacker’s decision‑action cycle has significantly accelerated. ASIO has noted that Australia has entered a more vulnerable security period, shaped by emerging threats with increasingly concerning trajectories, reflecting a security climate that is becoming more complex and less predictable (Australian Government, 2025). Since 2014, this evolving landscape has been characterised by a marked shift towards low-cost, high impact attack methods, with offenders increasingly relying on readily accessible weapons such as knives, vehicles, improvised explosive devices and basic firearms, often acting alone and with minimal forewarning.

At the same time the ideological profile of offenders has broadened. Instead of acting under the direction of organised extremist groups many individuals now mobilise around mixed ideological influences and grievance-driven motivations, a pattern that has become especially pronounced among younger cohorts and has complicated early detection efforts.

In this context, the December 14, 2025, Bondi Beach terrorist attack serves as a critical case study demonstrating how these evolving dynamics manifest in practice. The tragedy, carried out during a Hanukkah celebration attended by approximately one thousand people, involved two gunmen using legally acquired longarm weapons to deliberately target Jewish Australians, resulting in at least fifteen fatalities and dozens of injuries. The offenders also deployed improvised explosive devices, reinforcing the growing trend towards simple, low-cost, high impact operations within open and highly accessible public settings. The attack further highlighted the operational challenges posed by lone actor or small cell mobilisation, as one offender had minimal pre-incident indicators visible to authorities, aligning with ASIO’s warning that contemporary radicalisation is faster, more fluid and more likely to emerge from hybrid grievances rather than traditional extremist hierarchies. Throughout this ongoing shift, crowded places continue to represent the most attractive targets due to their accessibility, predictable footfall and the potential for high casualty outcomes, making locations such as shopping centres, major transport interchanges, largescale event precincts and places of worship particularly vulnerable in the absence of robust, proportionate protective security arrangements.

Behavioural and Activity Indicators Prior to an Attack

The attack planning cycle generally progresses through observable and behaviour-based stages that create important opportunities for early detection and intervention. When these signals are missed, an offender is more likely to advance along the mobilisation pathway without scrutiny, increasing the chance of an attack being carried out with limited or no warning. The events at Bondi Beach on 14th December 2025 illustrate this risk. Despite having previously come to ASIO’s attention, the attacker was not kept under active, continuous surveillance due to the sheer volume of national intelligence triage. This resulted in intelligence gaps that, in hindsight, proved significant (ASIO, 2025). Post incident reviews emphasised that the very large number of individuals assessed by national security agencies, most of whom never progress to an imminent threat, creates structural pressures that can limit sustained monitoring. These pressures can allow some individuals to continue radicalising and developing operational capability without timely detection.

Strengthening prevention therefore requires a coordinated, whole-of-government approach that improves prioritisation and broadens the capacity to identify and disrupt emerging plots. Community engagement and interagency cooperation are central to this effort. Families, friends and local observers often recognise concerning behaviour-based shifts before authorities do, so public vigilance remains essential. In Australia, citizens are encouraged to report suspicious conduct to the twenty-four-hour National Security Hotline, whether it involves testing protective measures, expressing extremist intent online or acquiring unusual materials (Australian Government, National Security, 2024). According to ASIO, even minor reports can become vital pieces of a broader intelligence picture. Many lone-actor offenders display clear behavioural indicators long before they act, such as growing fixation on extremist grievances, the leakage of violent intent or unusual inquiries about site security. Educating the public and frontline professionals about these pre-incident warning signs has therefore become a strategic priority, improving the likelihood that concerning behaviours are recognised and escalated before planning matures into operational action.

Protecting Crowded Places

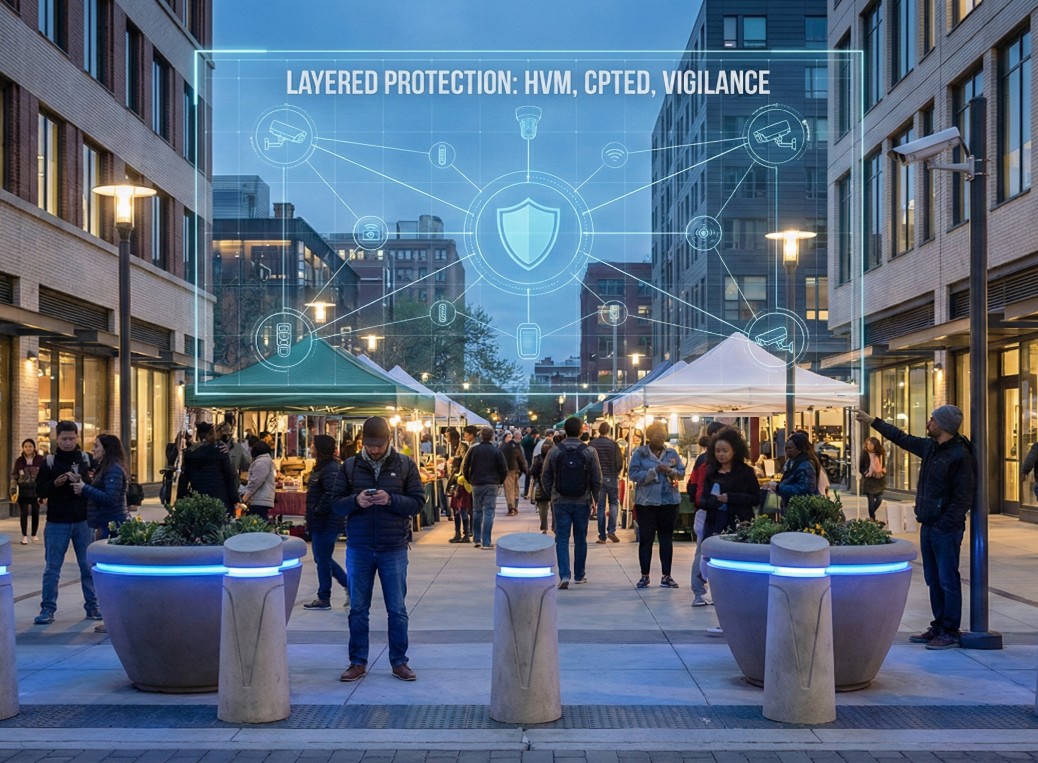

Protecting crowded places relies on a layered, design led approach in which owners and operators carry the primary responsibility for ensuring safe and resilient environments, including a duty of care to take reasonable steps to protect workers, visitors and the public from foreseeable threats such as terrorism (ANZCTC, 2023). Effective protection begins at the planning stage, where standoff distances, traffic management treatments and Hostile Vehicle Mitigation (HVM) measures form the essential first line of defence against vehicle borne attacks. National guidance, including the Australian Government’s Hostile Vehicle Guidelines for Crowded Places, identifies integrated physical controls such as barriers and traffic separation treatments as critical for reducing vulnerability in locations that attract large gatherings (ANZCTC, 2023). These measures are strengthened by technological systems such as active video surveillance, analytic alarm detection and structured access control, all of which contribute to a flexible and adaptable protective security posture.

Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design (CPTED) overlays add another important layer by shaping the built environment to discourage hostile intent and reduce opportunities for covert movement. The European Union Agency for Law Enforcement Training highlights how CPTED improves the protection of public spaces by enhancing natural surveillance, applying spatial criminology principles, reinforcing territorial boundaries and improving visibility so that suspicious behaviour can be detected more easily (CEPOL, 2024). When CPTED is combined with broader measures such as HVM and access control, sites become significantly harder for offenders to exploit while also supporting faster and more coordinated responses during an unfolding incident. In summary, safeguarding crowded places requires more than isolated physical or technological measures. It relies on the coordinated application of layered protective design, informed risk planning and CPTED principles that strengthen natural visibility and reduce opportunities for hostile activity.

Conclusion

Australia’s evolving threat landscape makes early recognition, informed design and shared vigilance more important than ever. The Bondi Beach attack showed how quickly violence can unfold and how subtle pre-incident signals can be missed, reinforcing the need for stronger behavioural awareness, smarter protective design and consistent public engagement. By combining layered security measures, CPTED led environments and a community that knows when and how to report suspicious behaviour, crowded places become significantly harder to exploit. Protecting these spaces is not the task of any single agency or operator. It is a collective responsibility that strengthens national resilience and helps ensure Australians can continue to gather, celebrate and live freely with confidence and safety.

References

- Australian Government. (2025). Current national terrorism threat level. National Security. https://www.nationalsecurity.gov.au/national-threat-level/current-national-terrorism-threat-level

- Australian Government, National Security. (2024, December 11) Report suspicious behaviour. https://www.nationalsecurity.gov.au/what-can-i-do/report-suspicious-behaviour

- Australia–New Zealand Counter-Terrorism Committee. (2023). Australia’s strategy for protecting crowded places from terrorism. Australian Government. https://www.nationalsecurity.gov.au/crowded-places-subsite/Files/australias-strategy-protecting-crowded-places-terrorism.pdf

- Australia–New Zealand Counter-Terrorism Committee. (2023). Hostile vehicle guidelines for crowded places. https://www.nationalsecurity.gov.au/crowded-places-subsite/Files/hostile-vehicle-guidelines-crowded-places.pdf

- European Union Agency for Law Enforcement Training (CEPOL). (2024). 3038/2024/WEB: Crime prevention through environmental design (CPTED). https://www.cepol.europa.eu/training-education/3038-2024-web-crime-prevention-through-environmental-design-cpted

- National Native Title Tribunal. (2024, August 7). ASIO update: Australia’s national terrorism threat raised. https://www.nntt.gov.au/News-and-Publications/latest-news/Pages/ASIO-update.aspx